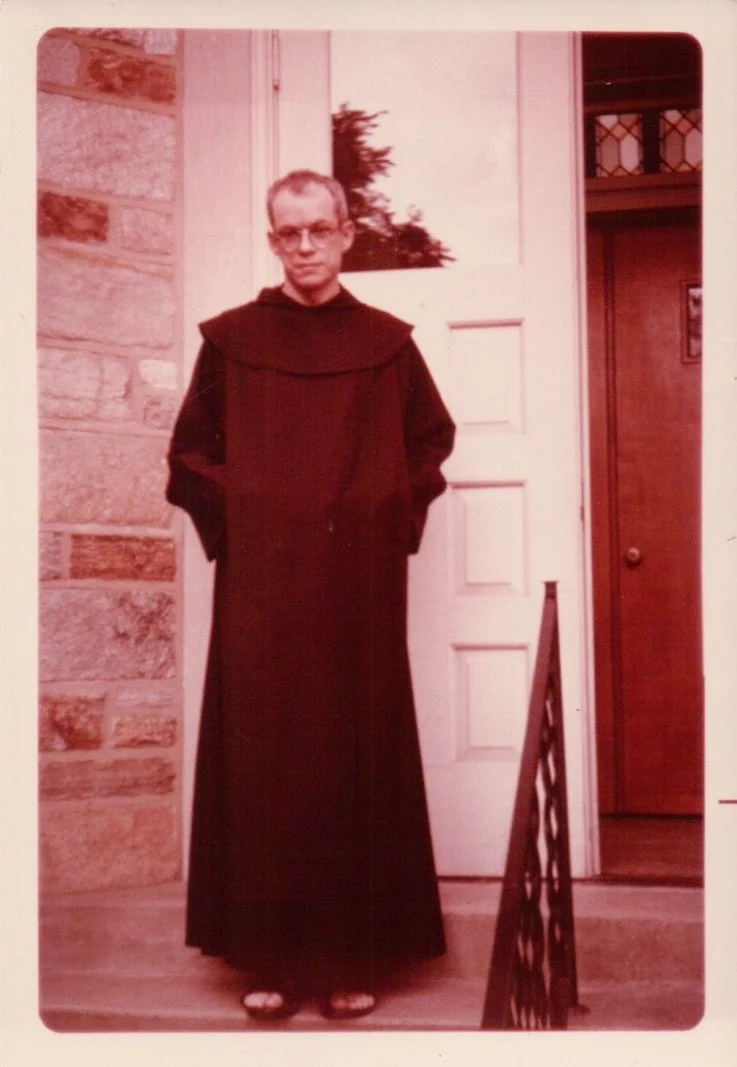

Fr. Kieran (Thomas Morgan) Kavanaugh of the Cross

Birth: February 19, 1928

Milwaukee, WI

Profession: August 27, 1947

Ordination: March 26, 1955

Death: February 2, 2019

Thomas Morgan Kavanaugh was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on 19 February 1928. After attending Archbishop Messmer High School in Milwaukee, he entered the novitiate of the Discalced Carmelite friars in Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1946. During his novitiate year, the Brookline community received a pastoral visitation from the order’s Spanish general, Fr. Silverio of St. Teresa, the great Carmelite historian and editor of the writings of Sts. Teresa and John upon whose scholarship Kieran would draw heavily in later years. On 27 August 1947, he professed his first vows of poverty, chastity, obedience, and humility, taking the religious name Kieran of the Cross after the saintly Irish founder and abbot of Clonmacnois, a famous center of holiness and learning in sixth-century Ireland. Following the novitiate, he returned to his native state to begin his studies for the priesthood in the Carmelite house of philosophy at Holy Hill, Wisconsin, forty miles northwest of Milwaukee. Kieran’s student master at Holy Hill was Fr. John Clarke, who would later join him in the translation ministry with his translations of the writings of St. Thérèse of Lisieux.

In August 1950, Kieran made his solemn profession of vows at Holy Hill’s Shrine of Mary, Help of Christians. His superiors then sent him to Rome for theology studies in the Discalced Carmelite International College of St. Teresa. On the college’s faculty at this time were Gabriel of St. Mary Magdalene, the renowned professor of spiritual theology, and the young Tomás Alvarez who would become one of the world’s leading experts on St. Teresa. Among the students were Spaniards Federico Ruiz, Eulogio Pacho, and José Vicente Rodríguez, all later to distinguish themselves as St. John of the Cross scholars. In Rome, Kieran wrote “The Christology of St. John of the Cross” for his licentiate in sacred theology and was ordained to the priesthood on 26 March 1955. He was twenty-seven years old.

Before leaving Europe, Fr. Kieran spent one year in the desert monastery of the Discalced Carmelites in Roquebrune-sur-Argens in southern France. A “desert” in the Carmelite tradition is a community of friars devoted exclusively to the contemplative life without involvement in external pastoral ministry. Its purpose is to preserve within the order both the early eremitical life of first hermits on Mt. Carmel in the Holy Land during the thirteenth century and the contemplative spirit of the sixteenth-century Spanish Carmelite reformers, St. Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross. At Roquebrune, situated in the rough foothills above the French Riviera near Fréjus and Saint-Raphaël, where the French-speaking provinces of the Discalced Carmelites maintain a desert in the chapel and hermitages of a former Camaldolese monastery, Kieran drank deeply of Carmel’s contemplative waters.

Fr. Kieran returned to the United States in 1957. Shortly thereafter he was assigned to the College of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel, the Discalced Carmelite house of theology in Washington D.C., to teach both dogmatic and spiritual theology and to be the director of students. In the Washington community at that time was Fr. Otilio Rodriguez, O.C.D. Newly arrived from Spain, a protégé of Fr. Silverio, Fr. Otilio was a historian of the Carmelite order and dedicated student of the writings of St. Teresa of Avila. Eager to see the Teresian Carmelite heritage spread in the United States, Fr. Otilio recommended to Fr. Kieran that he translate the writings of St. John of the Cross for Americans. Initially, Kieran resisted, claiming insufficient knowledge of Spanish. After Otilio reassured Kieran that St. John’s Spanish is not difficult and that, in addition, he would help him, the two friars began the translation in the fall of 1957.

The translation proved more difficult than Fr. Otilio imagined. What he thought could be completed in a few months took five years. Nonetheless, in 1964 Doubleday, the large secular publishers in New York, together with Thomas Nelson in England, published The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross, translated by Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D., and Otilio Rodriguez, O.C.D, with introductions by Kieran Kavanaugh. For the first time, readers in the United States had a modern American translation of the complete writings of the Spanish mystical doctor of the church in one 740-page volume. In addition, Kavanaugh and Rodriguez’s work reflected the most recent research in the life and writings of St. John, a benefit not present in the earlier translations by the Englishmen David Lewis in the second half of the nineteenth century or E. Allison Peers in the 1930s. Also, being Carmelites themselves, the ones for whom John originally wrote, the translators had insights into the saint’s words that came from living daily the way of life he was promoting in his writings.

In 1979, the Institute of Carmelite Studies published a second edition of the translation that included two hitherto unknown autograph letters of St. John discovered after 1964. In addition to stylistic and editorial improvements to the original translation, the translators also added a twenty-two page topical index and an index of Sacred Scripture. A decade later, in preparation for the fourth centenary of the death of St. John of the Cross in 1991, Fr. Kieran prepared a revised edition of the translation incorporating the results of the latest sanjuanist scholarship, adding footnotes that included helpful cross-references and a glossary of St. John’s terminology. He also revised the text, replacing the generic masculine with gender-neutral language, while preserving John’s references to God and Christ in masculine nouns and pronouns. Over the last forty years, this translation in its three editions has sold an average of 360 copies a month.

With their translation of St. John widely accepted by both scholar and general reader, Frs. Kieran and Otilio turned next to translating the writings of St. Teresa into American English. In the years since they began their collaboration, the Discalced Carmelites had closed their theological college in Washington and Kieran was now teaching spiritual theology at Catholic University of America. With the decision in 1972 to translate St. Teresa, he left the university to concentrate on his collaboration with Fr. Otilio in the challenging task of translating St. Teresa, a writer more prolific and complicated than John of the Cross. The Institute of Carmelite Studies published their translation of The Book of Her Life, together with her Spiritual Testimonies and Soliloquies, in 1976. This was followed in 1980 with their translation of The Way of Perfection, Meditations on the Song of Songs, and The Interior Castle. Finally, The Book of Her Foundations and minor writings, including her poetry, appeared in 1985. In each of these three volumes, Kieran wrote the introductions that provided readers with valuable historical and doctrinal background for understanding St. Teresa.

In the late 1960s, Fr. Otilio was called to Rome to head the Teresian Historical Institute at the Discalced Carmelites’ International College, now named the Teresianum, where he was also later to serve as rector. He and Kieran continued their collaboration by mail and during the summer months when Otilio returned home to the United States. From this point on, however, Kieran assumed more of the responsibility for the translations, especially as Otilio’s health began gradually to fail. When Otilio died in 1994 at the age of 83, his dream of promoting the Teresian heritage in the United States was largely fulfilled. At the time of his death, people not only in America but also throughout the entire English-speaking world were reading the Kavanaugh and Rodriguez translations of the writings of St. Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross.

Still, one significant part of St. Teresa’s literary legacy— her letters— remained to be translated into American English. Teresa wrote thousands of personal letters, of which some 468 still exist. Considered by John Tracy Ellis, the late American church historian, to rank among the masterpieces of Catholic world literature, these letters reveal the woman Teresa in all her humanness in ways that her writings on prayer and Carmelite life do not. Now without Fr. Otilio, but with his skills as a translator finely honed and his reputation as a Teresian scholar firmly established, Kieran began in the early nineties to translate St. Teresa’s letters. He has been assisted by Mrs. Tina Mendoza, who has compared his translation of each letter with the original Spanish, frequently suggesting more accurate renderings, and Dr. Carol Lisi, who provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript for publication. The first volume, consisting of 224 letters written by Teresa between 1546 and 1577, together with an introduction and brief biographical sketches of her correspondents and other persons mentioned in her letters, appeared in 2001. In 2007, ICS Publications will publish the second volume containing the translation of St. Teresa’s remaining letters, thus concluding the major work of Kieran’s priestly life, fifty years devoted to translating over 2500 pages of the complete works of John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila into standard American English.

To the members of his province, community, and especially, the Institute of Carmelite Studies, Kieran has become an older brother who daily shares his life with us, advising, encouraging, supporting, and inspiring us with his quiet presence, wise words, and good example. His legacy to our order will undoubtedly be his fidelity to the prescription in the ancient Carmelite Rule of St. Albert that calls each of us “to remain in or near one’s cell, meditating day and night on the Law of the Lord and watching in prayer unless otherwise justly occupied.” Kieran’s fidelity to this directive has been a main source of his productive life. Although he obtained a licentiate in theology during his early years in Rome and taught spiritual theology for several years at Catholic University of America, Kieran’s work has not been centered primarily in academia. Rather, his scholarship, translations, writings, and prepared conferences, preaching, and retreats have come from his devotion to his cell. He has thus left an example for us of the immense good for the order and the Church that results from following the ancient monastic custom of prayer and study in the quiet of one’s own cell.